The Discipleship Spiral: Doing to learn, and learning to do.

Some of you will be familiar with Grant Osborne’s work, The Hermeneutical Spiral. For those of you who are not, hermeneutics is the fancy name for interpreting the Bible, and Osborne wrote a book where he compared the process of interpretation to a spiral. The reader spirals back and forth from the text of Scripture to the context of everyday life, examining each in light of the other and spiraling upward to clearer and clearer understanding of both.

Discipleship works the same way.

In 1984, an educational scholar named David Kolb published a theory about how people learn. His goal was to highlight the extreme significance of experience in learning. Kolb claims that people learn through acquiring new concepts that are usually abstract in nature but can be applied to real life circumstances. In other words, new knowledge is best gained when abstract concepts can be put into practice. The reason people want to learn, in Kolb’s theory, comes through having new experiences that demonstrate a need for new concepts.

Kolb points out four stages in the learning process that apply nicely to discipleship. He claims people learn by first having a concrete experience. This leads to a need to reflect on that experience followed by the development of new concepts. In order to know if these new concepts are correct, the individual must then experiment or test them through another experience. This process, repeated over and over again, spirals the learner upward through more experiences and better knowledge.

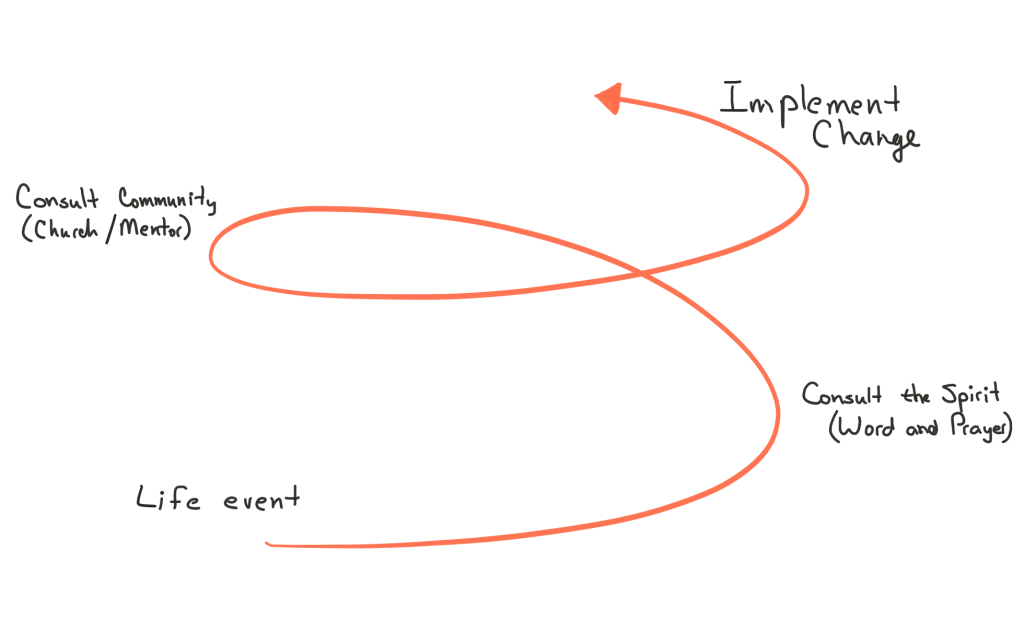

The idea looks something like this:

Think about learning to drive a car. Would anyone ever say they learned to drive by reading that booklet the DMV gives people to study for their license? Of course not. People learn to drive by driving. It is a concrete experience behind the wheel that goes well, or not so well, which causes the new driver to reflect on the process, create new concepts, and apply them the next time. Oh, and we would never put someone behind a wheel with no experience and not have a coach in the passenger seat. That just sounds absurd.

It is process learning. People can hear facts all day in the classroom and leave with little formative change in their life. We have all sat through an hour lecture and left not remembering any of it. This is no less true when it comes to discipleship. When our sole means of discipleship is cognitive instruction, we only focus on the filling of heads, not the changing of lives. If we realize the extreme importance of experiences in the learning process, then discipleship can spiral through life experiences and guided instruction.

Of course, discipleship is more than coffeeshop conversations and small group book studies. Discipleship is a process by which we become more like the person we follow. We fall into his footsteps. It is an active, lifestyle obedience that does not simply know all that Christ has commanded but obeys it as well. Truly, discipleship is being on mission and taking someone with you.

Much can be gleaned from Kolb when it comes to discipleship. His four stages apply well and we could even speak of a discipleship spiral that takes the disciple through increasing levels of experience and knowledge. Our discipleship models must account for experience as instigator and the Holy Spirit (along with Scripture and church) as the tutor.

Think of it like this:

Imagine discipleship that starts not in a Sunday school classroom or at a coffee shop table but through the experience of sharing the gospel with someone or counseling them in godliness. What if the very first thing we did with that young man or woman who asks us to disciple them was to take them to share the gospel? That would turn most discipleship models on their head. Traditionally, we learn first, in a classroom, and then tell our students to go apply what they learned. Some might even do it. But, basing learning on experience would take people out to share their faith (or practice hospitality, generosity, etc.) and then gather together to conceptualize and ultimately get better at the practice.

Practice necessitates instruction, not the other way around. In this model, gone is the idea of learning facts that do not translate into real life practice. Instead, practices determine the concepts that are learned, and what is learned makes the practice better than before.